Keeping it real – and local

January/February 2022 California Bountiful magazine

Cheesemakers maintain longtime partnership with region's dairy farmers

Story by Ching Lee

Photos by Fred Greaves

When Ben Gregersen and John Dundon first started making cheese together, their use of old-fashioned methods and simple ingredients earned them a following at farmers markets.

Twenty-five years later, the owners of Sierra Nevada Cheese Co. in Glenn County are helping to keep the tradition of dairy farming alive in a region that's been moving toward tree nuts.

Even as they continue to grow their brand and expand their product offerings—outgrowing their name as just a cheese company—Gregersen and Dundon have remained loyal to the local farmers who produce the milk. By purchasing from them, Sierra Nevada maintains close ties to its key ingredient, whether it's cow or goat milk. As the one remaining cheese plant in the county, the company also provides a viable future for area dairies whose milk might otherwise be without a home.

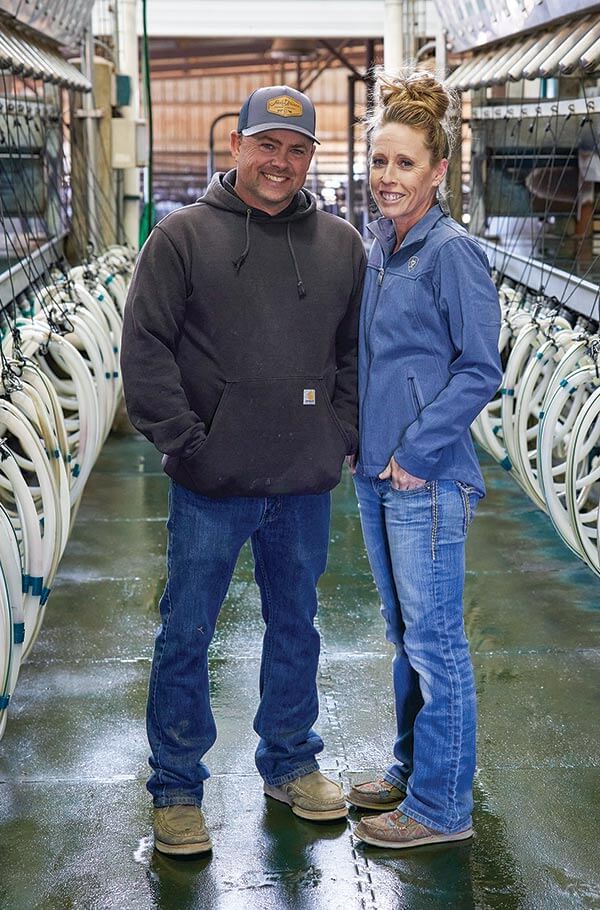

"They're kind of rekindling a little bit of a fire for milk," said dairy farmer Jake Zuppan, whose family produces cow and goat milk for Sierra Nevada.

Perhaps it's fitting that the company now occupies what was once the Glenn Milk Producers Association creamery in Willows. The farmers cooperative built the plant in 1958 during an era when milk was the region's second-highest grossing agricultural commodity, after rice. Today, almonds and walnuts take the top spots.

Gregersen and Dundon purchased the vacant property in 2003 when they needed more room to store the growing volume of cheese they were making, which by then had begun appearing on store shelves.

"After we got out to the retail stores, we grew fast—for us," Gregersen said.

How it all began

The duo met while they were working for Gregersen's family creamery in Sacramento. Originally dairy farmers from Denmark, Gregersen's parents owned several dairy processing businesses in the Sacramento area in the 1960s. At one point, they ran an ice cream factory and three so-called drive-in dairies (actually small creameries), each that processed and sold dairy products and milk under one roof. Imagine a modern drive-thru with milk processing in the back and people taking orders up front.

It was at one of these creameries where Gregersen and Dundon first tinkered with making traditional farmhouse-style cheeses in micro-batches using no gums, stabilizers, preservatives, artificial flavors or added sugars—the same way their cheese is made today.

Gregersen had studied cheesemaking in Denmark and Canada and said he would "talk John's ear off" about it, adding, "the more I got into it, the more I knew that's what I wanted to do."

"Farmers will tell you, once you've got milk in your blood, it just stays with you," he said. "I think John and I had that."

Dundun did not come from a dairy background but got into the business working at a creamery in Mount Shasta right out of high school and later for Gregersen's father. He later spent two years working at New Hampshire-based Brown Cow, where he learned to make yogurt and other cultured products, before moving back to the Sacramento region.

By then, the Gregersens' drive-in business had become more of a distributor for other dairy processors. This opened the door for Gregersen and Dundon to use the small processing room in the back for making cheese and other products. In 1997, they decided to go into business together—delivering milk by day and making cheese by night.

Making the move to Glenn County

"We were making it with our own hands, just a step up from your kitchen kind of thing when we started in the back room," Gregersen said. "We liked the flavor. Everything tasted much better."

For the first two to three years, they sold their products at farmers markets, where their cream cheese became an instant hit.

"It was the farmers markets where people were coming back every weekend to look out for our product," Gregersen said.

The partners said the reason they moved the company to Glenn County was for the region's milk, which came from more than 20 dairies in operation at the time. More important, they wanted to work with dairies that could provide grass-fed milk, which Gregersen said was "right up our alley."

Today, Sierra Nevada markets a line of products called Graziers, named for farmers who graze livestock on pasture, noted Meghan Rodgers, the company's sales and marketing manager. Products labeled as such are made with milk from grass-fed cows. The company also makes a variety of organic dairy products, which already come from cows raised on pasture and that meet national organic standards.

Poised for growth

Because his family produces milk for Sierra Nevada—and earns a premium for it—dairy farmer Zuppan said his family has returned to pasturing their cows, which they moved away from years ago when they converted their farmland to grow feed crops. What they couldn't grow, they had to buy. Cows don't produce as much milk on grass, he noted, but the money he now saves on not having to buy as much feed has made "a huge difference."

"Now the incentive to go grass makes sense," he said, adding that the Graziers program taps into a growing trend of people "really trying to pay attention to what they're eating."

The dairy, based in Orland, still ships some of its milk to a national dairy cooperative. But that milk must be hauled all the way to Alameda County; when the co-op closed its Glenn County cheese plant in 2019, more dairies in the region exited the business.

Zuppan said he thinks his family has been able to survive challenging times in the dairy business because of how it has diversified, such as expanding to produce goat milk for Sierra Nevada. He said he appreciates the "warm, fuzzy, small-town feel" of the company and stands ready to grow with it.

"I want to be first in line to fill that void," he said. "We don't want to flood them with milk, but when they want more, I want to be able to give it to them."

When Ed and Sarah Fumasi began shipping milk to Sierra Nevada 13 years ago, they were raising about 600 goats; now the herd has grown to 1,600. Located in Artois about 4 miles from the Sierra Nevada plant, the dairy began shipping pastured cow's milk to the company about two years ago. Milking about 130 cows, Ed Fumasi said they wouldn't be able to stay in business with such a small dairy if they sold their milk to conventional markets. But with the premium they receive through the Graziers program, he said, "it makes it pencil out."

He added, "We take care of them, and they take care of us, so it's kind of a partnership."

Flavor 'starts with the farmer'

As the company grows, Gregersen and Dundon acknowledge that they may need to keep their options open and look to farms outside the region, such as for organic milk, which now comes from California State University, Chico. But they agree that their partnerships with local farms remain a bedrock of their business. The flavor that people respond to in their products "starts with the farmer," Gregersen said.

"We wouldn't have it any other way," Dundon said of Sierra Nevada's small-business, keeping-it-local mindset. "We're in a partnership with the farmers. They're just as important as we are. We promote them because they're the backbone of our country."

Rodgers said Sierra Nevada's "whole vision" has been to connect the farm to its products and "to allow the consumer to feel confident about where their milk is being produced, where it's being processed."

"We're really happy that we're able to achieve these partnerships with these local dairies, where we can sustain each other and offer them a way to survive the dairy business and be in a niche market—and also provide them a great deal of pride," she said. "When I talk to them, they know where their products are going, and they get to see it on the shelf."