The real deal

January/February 2023 California Bountiful magazine

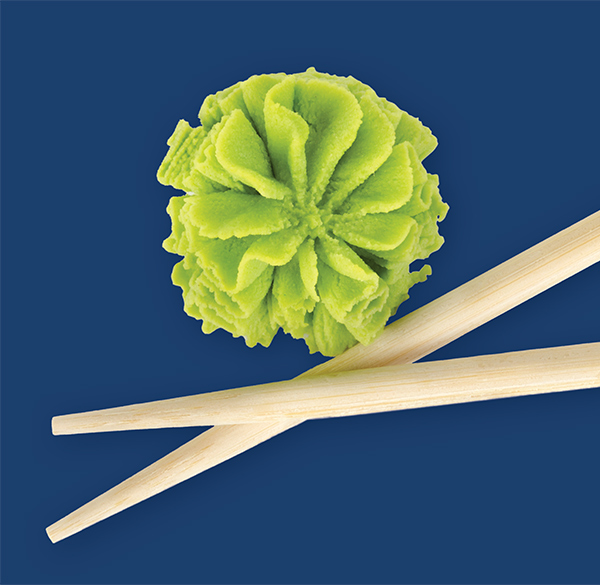

Farm grows genuine wasabi,

not dyed-green horseradish

Story by Linda DuBois

Photos by Lori Eanes

Electrical contractors Jeff Roller and Tim Hall were eating a sushi dinner after work one night in 2010, when the conversation turned to the pungent green condiment on their plates.

“You know, this wasabi we’re eating isn’t really wasabi,” Hall commented.

“I didn’t have a clue,” Roller says, referring to the fact that what most Americans call wasabi is instead a concoction of horseradish and green food coloring, often flavored with mustard powder or other spices—not the traditional Japanese rhizome.

Unlike horseradish, a root, wasabi is a plant stalk that continually creates new leaves at the top and loses old leaves, like a palm tree trunk. When ground into a paste, it gives diners’ nasal passages a similar blast of heat, but quickly fades to a milder, sweeter aftertaste.

Looking back on that dinner, Roller says that simple comment by Hall sparked an idea that led the business partners into a whole new adventure.

“During the recession, we were getting underbid for a lot of electrical work and were growing more and more frustrated and we kept saying we needed to have a niche, a specialty,” Roller recalls, “and then we just kept thinking about wasabi.”

So, they researched and learned that hardly anyone was growing it commercially in the United States.

“We started going around to restaurants and asking the chefs, ‘If we could grow real wasabi, do you think we could sell it?’” Hall says. “And they always said, ‘Yeah, because it’s really hard to source—but I don’t think you’ll be able to grow it in California.’”

The chefs knew wasabi needs year-round cool weather, takes at least two years to reach maturity and is more vulnerable than most crops to pests, viruses and root pathogens.

Hall and Roller just took that as a challenge.

So, even though Roller had no farming experience and Hall didn’t have any other than working summers as a youth on an orchard, they decided to give it a try.

Rocky start

Roller, of Oakland, and Hall, then of San Francisco, found land in Half Moon Bay, a small San Mateo County coastal town with a climate similar to the region in Japan where the crop flourishes. The site also came with greenhouses, a huge plus since wasabi prefers indirect sunlight and needs controlled moisture. In 2011, they launched Half Moon Bay Wasabi and planted their first crop in a 4,000-square-foot space.

They soon would be glad they had kept their day jobs.

They had so many problems that they had to pull up and throw away all 800 plants and start over. “It’s not like there’s a guidebook on how to grow this stuff and there’s not much information coming out of Japan,” Roller says. “We learned everything the hard way.”

One of the biggest hurdles is the lengthy growing cycle. “Stresses just manifest themselves into diseases a lot easier when plants are older,” Hall says. “You’ve spent all these resources—water, fertilizer, rent—and so when you start losing plants after a year or 14 months, it can be pretty devastating.”

Through a process of extensive trial and error, they had a tiny bit to sell after two years and got their first real crop after three.

Success at last

The upsides to growing wasabi are the perennial plants can be grown and harvested year-round and can be multiplied. “Mature plants put off shoots. You can pull them and replant them,” Roller explains. “Sometimes we do that and sometimes we purchase plant starts.”

To curb problems, they use natural predators and barriers to thwart hungry pests and carefully manage irrigation—wasabi is vulnerable to even slightly too much or too little water. They regularly walk the rows, checking each plant for problems or changes.

Their care has paid off. Today, the plants fill three greenhouses over a half-acre.

With help from one to two employees, they do their own harvesting, packing and shipping and Roller often delivers to a few Bay Area restaurants on his way home from the farm.

They harvest every Monday and sell anywhere from 20 to 100 pounds a week at $80 to $95 per pound, mostly to high-end Japanese restaurants willing to pay the price for the real stuff. They also sell the leaves, often used as a garnish or pickled in a traditional Japanese side dish.

Since they started, they’ve sold to about 200 restaurants throughout the country.

Hot commodity

One of them is chef Sylvan Brackett’s Rintaro, a San Francisco Japanese restaurant in the izakaya style, a casual bar-like eatery with a tasting menu of small dishes.

Brackett serves wasabi regularly with his sashimi and sometimes with tofu, shellfish or chicken dishes and notes it’s also good with steak.

Brackett opened Rintaro in 2014 after cooking at Chez Panisse in Berkeley and restaurants in Japan (where he was born) and running his catering company, Peko Peko. When developing the concept, he was “trying to think of California as a region of Japan and what that would look like.” Wanting to buy from local farms, he says he was thrilled to discover Half Moon Bay Wasabi.

Brackett suspects most of his customers had never eaten real wasabi before coming into his restaurant, but he says they seem to notice the difference between it and the horseradish they’re accustomed to. “We get a lot of people commenting that it’s delicious,” he says.

“They both give you the heat, but wasabi has a natural sweetness to it. It’s a more distinct and clear flavor—like you can taste it as a vegetable—and the texture is a little smoother.”

Preparation process

Wasabi’s heat comes from a gas that will dissipate if left uncovered for a few hours. So, when Roller delivers his wasabi, Brackett typically stores it in a covered container in the refrigerator or buried in ice, but doesn’t freeze it, which would alter the texture. He prepares a batch at the beginning of each dinner shift and another later, keeping each in a sealed container until ready to plate.

He uses the back of a knife to scrape off the skin of the wasabi (a peeler takes too much off). Then, he grates it on a sharkskin grater. “A sharkskin is very fine, almost like sandpaper and it yields a really smooth paste,” he says.

If preparing a small batch, often chefs will shave a little off the sweeter leaf end and then off the hotter root end and blend the two to maintain a uniform flavor.

Brackett says any leftover grated wasabi can be wrapped in plastic wrap and frozen “if you don’t want to waste it … but it won’t be the same as freshly grated.”

Brackett used to buy wasabi from Japan, “but it would show up just in terrible shape. It was just old, having gone through all the transportation.” Now he buys it exclusively from Half Moon Bay Wasabi, which ships it the same day it’s harvested.

He notes that he appreciates and admires Roller and Hall. “They chose one of the hardest things in the world to grow and they’re doing a really good job.”

What's the story on wasabi?

In the same family (Brassicaceae) but a different genus as horseradish, mustard and cabbage, wasabi has been growing wild, likely for thousands of years, along stream beds in Japan’s mountain valleys. It is believed to have been first eaten as a seasoning for raw fish and venison. The oldest record of wasabi being used as a food dates to the eighth century; cultivation in Japan dates to the 10th century.

“There are like 30 different cultivars of wasabi, but we really only have access to three or four of them here,” says Jeff Roller, who co-owns Half Moon Bay Wasabi with his business partner, Tim Hall.

Their farm grows Daruma, which is one of two main cultivars. “We’ve tried some other ones and that’s the one we had the most success with,” Roller says.

Because the crop is finicky about climate and growing conditions, their coastal farm is one of the few in the U.S. that has been successful. Other productive regions include the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest and parts of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the East.

Such scarcity makes the condiment expensive. So, an estimated 95% of U.S. sushi restaurants use a substitute made with dyed-green horseradish. The Japanese call it “Western wasabi.”