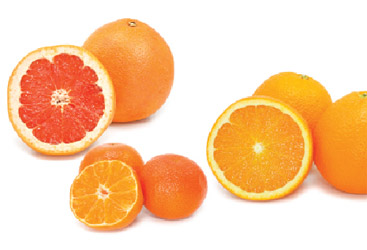

The history of citrus in California

Story by Ching Lee

California's citrus heritage has deep roots in what is now bustling downtown Los Angeles.

In the 1840s, it was the site of the state's first commercial citrus farm, planted by a frontiersman named William Wolfskill, considered to be the "granddaddy" of California's citrus business.

"When the Gold Rush of 1849 hit, there was a huge demand for oranges in the gold country because it was well established that fresh citrus was useful in combating scurvy," a vitamin-C deficiency, said Vince Moses, a historian on California citrus and former director of the Riverside Metropolitan Museum. "Wolfskill's business grew exponentially and established a market for citrus fruit."

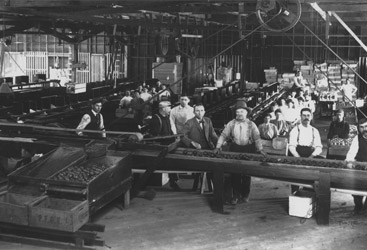

Photo Credit: Sunkist Growers

But long before citrus became a viable commercial crop for Wolfskill and other growers who followed, Spanish missionaries who settled in Southern California during the 1700s were already cultivating a variety of citrus fruit, believed to have originated from Southeast China thousands of years ago.

Wolfskill grew hundreds of lemon and orange seedlings, which he secured from the San Gabriel Mission. And while his early success showed that there was at least a regional market for citrus, it was not until the introduction of the navel orange in the 1870s that propelled the growth of California citrus, which fueled the economic and social development of California.

So called because the end of the fruit resembles a belly button, the navel orange was far superior to other varieties at the time because it was seedless, sweet and ripened in winter under California's Mediterranean climate.

The fruit was actually a mutation from an orange tree that grew in a Brazilian monastery. The U.S. Department of Agriculture obtained cuttings from this tree and in 1873 sent two or three starter trees to spiritualist and woman suffrage activist Eliza Tibbets in Riverside to see if they would grow.

Photo Credit: Sunkist Growers

"The trees produced these incredible oranges—huge golden globes that outshined every other citrus table fruit around," Moses said. "That was the key to the establishment of the California commercial citrus industry. Riverside really became the fulcrum for the development of that big market."

The navel also changed how farmers produce citrus and other fruit trees. Prior to the navel, citrus was grown mostly from seed, which meant the trees retained their biological diversity, bearing a hodgepodge of fruit that lacked standardization.

Because the seedless navel has no way to reproduce naturally, growers must assist Mother Nature by grafting bud sports to another tree's trunk or roots, a process that creates a clone of the original.

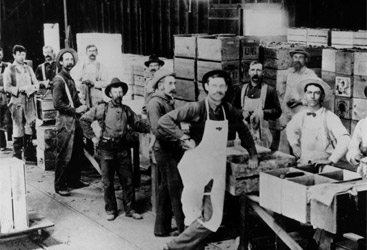

Photo Credit: Sunkist Growers

Today, nearly all of the navel orange trees grown in the state are descendants of the Tibbets' original trees. One of those trees, now 137 years old, still stands and bears fruit in Riverside, and has been designated as a California historical landmark.

Riverside remained the center of the navel orange business, which soared in the 1880s. The whole nation wanted California navel oranges, and with the establishment of the transcontinental railroad, growers were able to supply them.

"The railroad made it possible to get this fruit thousands of miles away to the big eastern markets—New Orleans, Chicago, New York," Moses said.

Demand for California citrus grew, along with the state's citrus acreage, as citrus quickly became the economic base for the Golden State. The citrus boom spurred California's "second" Gold Rush—only the new gold was orange.

With the rapid expansion of citrus production in the state, growers needed a more effective way to broker and market their fruit. As individual farmers, they were often at the mercy of wholesale agents and the railroads and paid hefty freight charges to ship their goods.

"The growers were being taken advantage of considerably by jobbers and those who were marketing the fruit, so much so that they were operating in the red," said Dick Barker, president and founder of Citrus Roots-Preserving Citrus Heritage Foundation. "So there was a need to associate and bring all the growers together so they could control the situation and at least receive a fair return for their products."

Photo Credit: Sunkist Growers

In 1893, they did just that and formed the Southern California Fruit Exchange, a cooperative known today as Sunkist Growers.

Capitalizing on the image of California as the land of opportunity and sunshine, the state's citrus sector became the first to use advertising to promote an agricultural commodity, and the orange became the perfect symbol for the sun and the Golden State, Barker said. The ads proved effective, and sales of oranges rose.

"That was the key to the whole industry," said Barker, himself a retired third-generation Sunkist grower. "It sent the momentum to sell fruit and was successful in marketing the fruit. From then on, advertising was the key to marketing citrus and the benefits from those ads were prolific."

By the early 20th century, with the state's citrus business thriving, growers lobbied for a research facility that could help them with production issues and grow a better crop. They got their wish in 1906, with the establishment of the Citrus Experiment Station, which became the foundation of the University of California, Riverside.

The Citrus Experiment Station, now called the Citrus Research Center and Agricultural Experiment Station, remains at the forefront of citrus genetics, breeding, physiology and postharvest studies, and has brought consumers new citrus varieties such as the Ojai Pixie tangerine, and most recently, the Gold Nugget tangerine. The university's Citrus Variety Collection also contains more than 1,000 different citrus types from all over the world and is the most comprehensive collection of its kind.

Today, California's citrus sector, valued at more than $1 billion annually, ranks second in the U.S. after Florida, which produces the most valencia oranges; those are the seeded oranges used mostly for orange juice. California is No. 1 in fresh-market oranges, most notably the navel, but also produces a significant share of the nation's valencias, lemons, grapefruit and tangerines.

With the rise of urbanization in Southern California, what was once the state's original "citrus belt" has gradually migrated north into the San Joaquin Valley.

"The industry has primarily moved out of Southern California because it became more profitable to grow houses than oranges," Moses said.

He laments that the region's citrus tradition and heritage may be rapidly disappearing as new residents move into the area that are unfamiliar with the importance of citrus.

"Contrary to popular argument, it was not real estate that built Southern California," he said. "It was really the viable economic foundation that citrus brought to the region. It was a renewable resource that kept pumping money back into this region for a really long time."

History of citrus at a glance

- 1769 While building the California missions, Father Junipero Serra also plants the first citrus seeds.

- 1840 Frontiersman William Wolfskill plants lemon and orange seedlings in what is now downtown Los Angeles. California's citrus business is born!

- 1870s Riverside couple Eliza and Luther Tibbets receive navel orange cuttings from Brazil. The trees thrive and word quickly spreads about the sweet, seedless fruit.

- 1877 The completion of the transcontinental railroad helps satisfy a national demand for navels and other California-grown citrus.

- 1893 Needing an effective way to market their citrus, farmers form the Southern California Fruit Exchange—a cooperative now known as Sunkist Growers.

- 1906 Farmers lobby for a research facility to help them grow a better crop. The Citrus Experiment Station becomes the foundation of the University of California, Riverside.

- Today California's more than $1 billion annual citrus business ranks second in the U.S., producing a significant share of the nation's navels, valencias, lemons, grapefruit and tangerines.

Ching Lee

clee@californiabountiful.com