Prized pepper

May/June 2023 California Bountiful magazine

Farmers hope popular Basque ingredient catches on in U.S.

Story by Ching Lee

Photos by Fred Greaves

If Krissy Scommegna could have it her way, jars of her chili powders would be as ubiquitous as salt-and-pepper shakers in every kitchen in America.

Well, she’s working on that.

The Mendocino County farmer specializes in growing chili peppers, most notably Espelette, a red chili pepper from the Basque region of France. Prized by chefs and a staple in Basque cuisine, Piment d’Espelette, as it is called in French, can be hard to find on this side of the pond. Lack of a local source inspired Scommegna to start growing the pepper herself—and making her own chili powder.

Her company, Boonville Barn Collective, which she operates with her husband, Gideon Burdick, is now the largest producer of Espelette peppers outside of France. Chili powder made from the peppers has also found its way into hundreds of restaurant kitchens across the country, with home cooks catching on.

“It’s an incredible pepper that I think gets overlooked because its high price makes it a chili that is not common in regular recipes that people use,” Scommegna says.

Her California-grown version of Espelette is marketed as Piment d’Ville, a nod to the Anderson Valley town of Boonville, where the farm is located. Because of the protected status of the celebrated pepper, only Espelette peppers grown in and around the French village of Espelette can be called Piment d’Espelette, or “pepper of Espelette.”

Moderately hot, slightly smoky with sweet and fruity notes, the versatile spice is used to season everything from eggs, meats and vegetables to soups, stews and dips. Sprinkling the vibrant reddish-orange powder on dishes also adds color without overpowering them with too much heat.

“It’s a flavor builder,” Scommegna says, noting that the pepper doesn’t add just heat, acid or spiciness to foods but rather “levels and layers to whatever you’re cooking.” In the Basque region, she points out, Espelette is often used in place of black pepper.

It started with chili powder

The spice was the “favorite secret flavor” of chef Johnny Schmitt, owner of the Boonville Hotel and Restaurant where Scommegna also worked as a chef. She says even though the farm-to-table restaurant grew plenty of its own vegetables and bought other ingredients from local farms, it had to import Espelette pepper—and it was expensive. She decided to try growing her own.

Her father, who owns a vineyard nearby, provided the land. She asked Nacho Flores, the vineyard’s foreman and a seasoned farmer, to grow about 50 plants in 2012. She says even though he had never grown Espelette peppers before, she thought the plant would do well in Anderson Valley because it has a climate similar to the southwestern region of France where the chilis come from. Both are in valleys connected to the ocean, lending to warm days and cooler nights.

She was right. That fall, Flores presented her with a tub overflowing with ripe Espelette chili peppers.

They experimented with different ways to dry and grind the peppers, ending up with about a pound or two of chili powder, most of which was used in the hotel kitchen. Each following year, they grew more and shared the product with friends and other chefs. Scommegna says she considered the project more of a side business at the time as she and Flores continued to experiment with growing the pepper and making the powder.

Heirloom beans and olive oil added

Meanwhile, she met Burdick in 2014 while pursuing her master’s degree in Boston. The two shared an interest in food. A business and economics major, Burdick had spent time on a farm in Italy raising pigs and growing olives and grapes. After moving back to the states, he worked for food hubs that marketed products for small and mid-sized farmers.

He moved with Scommegna to Boonville in 2019 to help run the farm, which produced its biggest crop that fall—from 65,000 plants that yielded 7,200 pounds of powder. That same year, Scommegna and Burdick formed Boonville Barn Collective.

“We were really excited about trying to find other producers to work with—meat producers and new restaurants—and expanding our distribution as much as possible,” Scommegna says.

Then the pandemic hit. The company went from filling regular purchase orders from food-service buyers to zero sales for months.

“We thought, huh, this is interesting,” Scommegna recalls. “It was a big realization that we can’t just grow one kind of chili on the farm.”

In addition to diversifying their crop mix, Scommegna and Burdick expanded their focus from selling mainly to chefs and restaurants to retail and direct-to-consumer sales via their website. The farm now grows 12 different varieties of chili peppers and a line of heirloom dried beans. Existing olive trees on the 7-acre property also allow the farm to make olive oil.

Powder adds ‘a little kick’

In making their chili powders, all steps are done on the farm—from saving seeds each year to growing, drying, processing and packaging the product. To maintain a personal touch, Burdick says they include handwritten notes to everyone who places an order, thanking customers for supporting the farm, “because that is what we are first and foremost.”

“We’re not the biggest farm in the world, but we’re doing something special here,” he says. “It means a lot when people support that and learn about what we do.”

Even with more than a decade of experience working with the peppers, Scommegna says “every year we learn something new.” Farm foreman Flores, whom Burdick describes as a “constant tinkerer,” says frost remains a big concern for the peppers. Having grown all kinds of crops in Mexico since the age of 12, Flores says he knew trying to tackle Espelette in Anderson Valley would be a challenge.

“I was worried about all those cold nights that we have up here,” he says. “Peppers are more for warmer weather.”

Patience is key, he says, and lots of tender loving care. Because of the region’s cooler temperatures, it takes the plants much longer to grow and its fruits to develop. But he says the results pay off.

“This is why we have this really nice profile of flavors and aromas in the peppers, because they have a really long (growing) window,” Flores says.

He says he likes to add Piment d’Ville to foods such as jicama, pepino, coconut and other fruits, as well as to dishes such as ceviche and tacos. But his favorite way to use it is on eggs.

“It’s nice to have a little spice early in the morning,” he says. “It’s just a little kick with flavor.”

Scommegna says sprinkling it on fried eggs or adding it to onions while sauteing are great ways for cooks to familiarize themselves with the flavor and qualities of Piment d’Ville. The pepper’s oils add richness and cheesy notes to dairy-based recipes such as cream sauce. The spice works well with roasted vegetables, she says, and can be bloomed in oil for basting chicken, fish and pork chops.

Pennyroyal Farm’s creamery, also based in Boonville, rolls one of its cheeses in Piment d’Ville. Chef and chocolatier Chris Kollar, who owns Kollar Chocolates in Yountville, makes an Espelette chili dark chocolate ganache for one of his truffles, which he garnishes with Piment d’Ville.

“When people say, ‘How do you use this?’ I respond, ‘On everything,’” Scommegna says.

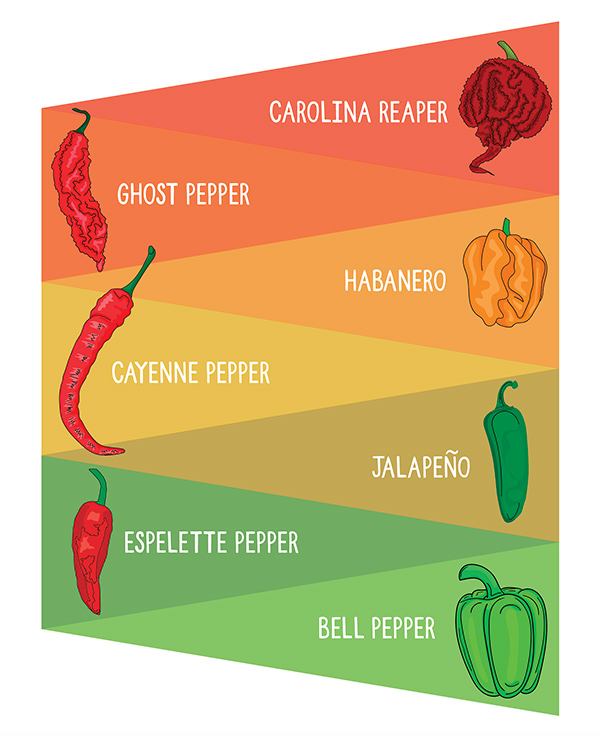

From mild to scorching

Chili peppers get their heat from the compound capsaicin. Depending on how much capsaicin a pepper has, it is classified as either a chili pepper or a sweet pepper, which has little or no capsaicin. A pepper’s heat is measured in units using the Scoville scale, named after its creator Wilbur Scoville.

For example, bell peppers have zero Scoville heat units, or SHU. Other mild peppers with zero to 500 SHU include mini sweet peppers, Lombardo, Shishito and Pepperoncini.

On the other end of the spectrum, the Carolina Reaper, officially the hottest pepper in the world, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, clocks in at 1.5 million to 2.2 million SHU.

Depending on growing conditions, Espelette peppers can range from 400 to 4,000 SHU. By comparison, poblano peppers measure 1,000 to 2,000 SHU; jalapeño, 2,500 to 8,000; Aleppo and chipotle, 5,000 to 10,000; serrano, 10,000 to 25,000; cayenne, 30,000 to 50,000; orange habanero, 100,000 to 350,000; and ghost pepper, 600,000 to 1.04 million.