Have shears, will travel

Stephany Wilkes left her high-tech job in Silicon Valley to shear sheep full time. Photo: © 2018 Paolo Vescia

As a knitter, Stephany Wilkes simply wanted to buy some local yarn.

Shortly after moving to the state in 2007, the San Francisco software developer was browsing the selection at a local yarn shop, excited to get her hands on wool from California sheep. After all, California is the nation's leading agricultural state and is a major wool producer—and yet, she couldn't find any local yarn.

"It just didn't make any sense," Wilkes said. "This is ground zero of local food, with all these farmers markets. California grows everything."

Little did she know her quest for California wool would inspire her to change the trajectory of her life and career—and in the process, find her true passion. After nearly 20 years working in the high-tech industry, Wilkes left Silicon Valley to become a full-time sheep shearer. She even wrote about the experience in her memoir, "Raw Material: Working Wool in the West."

With her shearing equipment and Mini Cooper convertible, Wilkes, left, travels to ranches such as Meridian Jacobs in Vacaville, right, which raises Jacob sheep, characterized by their horns, dark and light faces, and spotted bodies. Photos: © 2018 Paolo Vescia

Stepping into the ring

Having grown up in Detroit in an autoworker family, Wilkes said she was always conscientious about the importance of buying American-made products and its impact on the local economy. When she had trouble finding locally produced yarn, she thought there was a lack of demand for it, but she later learned the problem had more to do with the supply chain. One of the barriers to getting domestically produced yarn, she said, is a shortage of shearers to remove the wool from the sheep.

"There was this disconnect, and it's because of the shearing costs and because of how far you have to send (wool) to a mill," she explained.

Much of this revelation came in 2012, when she attended a symposium organized by the nonprofit Fibershed that brought together sheep ranchers, shearers and people interested in natural fibers. At the event, she heard owners of small flocks talk about how hard it is to find people to shear their sheep. A panel of "very big men who shear sheep" described the difficult, physically intense work they do.

"I thought, maybe this is something I could do, which is insane," she recalled. "I don't know why I thought this."

Though she doesn't have a background in agriculture and had never even pet a sheep, she decided to sign up for sheep-shearing school at the University of California Hopland Research and Extension Center in Mendocino County.

Students who've gone through the five-day course have likened it to boot camp because of the intense, hands-on training and physical labor involved, especially for those who've never handled sheep. Wilkes said nothing she had ever done before was as hard as shearing school.

"By Wednesday, I was really going to quit," she said.

She didn't quit, but she didn't do much shearing the first year after schooling. But then people started asking her to shear for them, mostly those with just a few sheep.

"I was so afraid," Wilkes said. "But then I thought: This is who you were supposed to be helping, and now you're in a position to help them, so you probably should."

Sheep rancher Robin Lynde examines wool from her Jacob sheep. Photo: © 2018 Paolo Vescia

Trying to keep up with demand

In the five years she's been shearing, Wilkes said she has not been able to keep up with the demand for her services. She's usually booked solid during the shearing season from January through June and rarely takes new clients. Though she continues to do some tech work during the summer when she's not shearing, Wilkes said choosing this career path was one of the best decisions she ever made.

"I totally love it," she said. "I get to go to ranches that are these really amazing, beautiful places. It's the best life I could ever ask for."

Sheep owners, particularly those with small flocks, have had trouble finding shearers for years—and the smaller their flock, the harder it is to get someone to shear for them because shearers are paid by the number of animals they shear, said John Harper, a UC livestock and natural resources advisor who has run the annual shearing program for nearly 25 years.

It used to be much more lucrative for professional shearers from countries such as Australia and New Zealand to travel to the U.S., he said, but limited work visas and poor exchange rates have dampened those prospects. The shrinking U.S. sheep population does not help.

Wool is carded, top left, to align the fibers in the same direction. It is then ready to be spun into yarn, bottom left. Handspinning techniques vary, but they entail twisting the fiber into a continuous thread by using a spinning wheel or spindle. Lynde, right, winds yarn into skeins. Photos: © 2018 Paolo Vescia

The only sheep-shearing school in California, the UC program was started to address the need for shearers and because "it's very hard to learn to shear sheep without a lot of oversight and instruction," Harper said. For years the program struggled to attract students, with attendance so low some years that classes had to be canceled. But that has changed. Not only have classes been full, they've been filling up within minutes of registration, Harper said.

"We've been attracting a lot of people who are in the millennial age bracket, especially females, because they want a job where they're the boss," he said.

Harper said shearers can earn $50 to $100 an hour shearing small flocks with an initial investment of $3,000 to $4,000 on equipment. Those who go through the UC training program typically learn how to handle and shear sheep, he said, although "they wouldn't be very good at it until they went out and got more practice."

Wilkes models wool garments made from Jacob sheep fleece. Photo: © 2018 Paolo Vescia

Connecting fibers

To find more hands-on experience with sheep before taking her first shearing job, Wilkes reached out to Solano County sheep rancher Robin Lynde, whose farm, Meridian Jacobs, is named for the rare breed of Jacob sheep she owns. Lynde runs a farm club that allows community members such as Wilkes to spend time on the ranch to learn about farming and raising sheep as a business.

"Most of them are in it for learning about sheep and about fiber," Lynde said of her farm-club members. "A lot of them are spinners. Some are people who think they might want to have sheep later on and want to find out whether they want to have sheep. But a lot of them know they will never have sheep, and this is the closest thing they'll get to having a farm."

Wilkes described her initial relationship with Lynde as that of student and teacher. She credits Lynde with teaching her "most everything" she knows about sheep behavior and care, pasture management, lambing, hoof trimming and what transpires in and around the barn. But the two quickly became friends because of their common interest in local fiber. Not only does Lynde sell wool from her sheep—which produce mixed, light-and-dark fleece unique to the breed—but she also teaches classes on spinning, weaving and wool dyeing.

Wilkes and Lynde both serve as officers for the Northern California Fibershed Cooperative, which provides an online marketplace for farmers and ranchers to sell their locally produced fibers and related wares. Being part of a movement that supports local fiber and the farmers who produce it has brought agriculture and culture to her clothing, Wilkes said.

"Now I have this wardrobe that reflects my landscape and the practices of the people who are caring for these animals," she said. "This is part of California culture—what these farmers are doing. It's part of my culture."

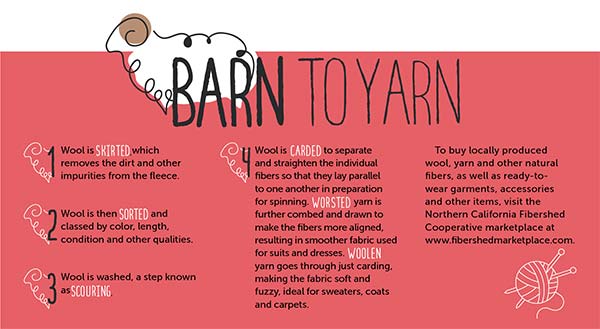

Barn to yarn

Though California remains the nation's No. 1 wool state—producing 2.5 million pounds of wool in 2017, or more than 10 percent of total U.S. wool production—only about 0.03 percent of California wool is processed in the state, according to a 2014 study by Fibershed, a California-based nonprofit that advocates for the creation and strengthening of regionally based textile systems.

U.S. textile mills used to process nearly all the wool produced domestically, but many of them have either closed or moved offshore. This gap in the supply chain leaves many sheep ranchers with no home for their wool. Small ranches that don't produce much wool often end up composting the fiber, or they pool their wool with others and then ship it to one of the few commercial wool-processing mills left in the country, usually on the East Coast.

These mills play a key role in the barn-to-yarn infrastructure. Before raw wool can be spun into yarn, a few steps must happen: